I didn't want to be caught alive. The story of Karel Kukal, Zdeněk Štich and refugees from shaft no. 14

In a black coat, black hat, and gray beard, he looked a little like a rabbi. He then said that there were eleven people on the run at the time, sometimes called twelve, but the twelfth was not one of them.

Memorial plaque from Slavkov, which commemorates political prisoners from Austerlitz shaft number 14 | photo: Post BellumThey reached the fields and meadows around Stanovice, where the firefight began and where the above-mentioned fell: "They are buried, ie rather buried in this cemetery. And they are also listed in the death book, but the place is not intentionally marked there. The commander of the escort who brought the corpses told the gravedigger to bury them on the way. For people to step on them. "

Karel Kukal lived in Switzerland at the time and was the only fugitive to be able to tell about the events of October 1951. Five men died at Stanovice. Two others were shot dead by police later in other places. Two were sentenced to death and executed. In addition to Kukal, Zdeněk Štich also survived, who was beaten so hard during interrogations that he collapsed and lost his memory.

Young Cookie and For Freedom magazine

Karel Kukal was born on November 27, 1927 in Prague Vinohrady. My father traded, had a grocery store, then a stationery store, and finally a deli in the Black Rose passage. Karel grew up with three siblings, in 1938 he started going to grammar school, during the occupation he transferred to business school.

Karel Kukal in the 1940s | photo: Post BellumWhen he finished it, he joined the company Marek a Čeleda, plastics press. As a boy he was a scout, he was nicknamed Cookie, and when the Germans banned scouting, he and his friends kept the unit secret; he also liked music and sang in the choir.

Shortly after the war, he became a member of the National Socialist Youth Organization, where he worked as a cultural officer. He was anti-communist and distributed white papers before the May 1948 elections. At that time, people could only elect a single candidate for the National Front, which was controlled by the Communist Party - or demonstrate disagreement with the situation by throwing in clean paper.

The Communist Party was an instrument of Moscow, and the young National Socialists often met with stronger resistance than the "national-front" party leadership. Kukal says he carried his views from his family: two of his uncles came to Russia and described the Soviet regime as mischievous.

Just before February 1948, he read an advertisement announcing that the Prague Theater would accept several members of the choir on May 5: he went to an audition, they told him that he was not singing badly and that he would receive a notification by post. Before it came, a coup broke out and the Communist Party began to build a totalitarian state based on the Soviet model.

Karel continued to meet with friends from the National Socialist youth: "We held on to each other and decided to do something against the new regime. And so we started publishing an illegal magazine called For Freedom. "

The leaflet magazine was created by a group of about five people, and was secretly printed on a bicycle style in the Marek and Čeleda offices. It was published in thirty copies, with five sheets containing articles written on the basis of information from Western radio. The authors chose pseudonyms - Kukal's name was Brodský. They disassembled the prints and distributed them to people they trusted.

Karel Kukal (Cookie) after the war photo: Post BellumOn June 11, 1948, she arrested the entire editorial board of the magazine Státní bezpečnost, this happened in connection with the case of Choc a spol. Karel Kukal says that they were betrayed by chance:

"There was a girl in our group, her name was Zdenka Hořčíková, who worked at the Central Secretariat of the National Socialists.

Even before February, angry members of the Communist Party began going there, joining the National Socialist Party - and demonstratively discarding their communist IDs. Zdenka took some of them then, that they could be useful. After the coup, couriers, agents from the West, began to come to Czechoslovakia. We met some of them, we took the communist ID cards, we exchanged photos and we gave them - so fake papers were created that could be useful to them.

Then, when someone shot Security Major Schramm, arrests began, and it was the people who had the ID from us that had something to do with this case. They wanted to run back abroad, but they caught them, found IDs with them and got them where they got them from. That's how it came to us. "

Kukala was taken secretly to Bartolomějská and from the beginning they treated him harshly during the interrogation:

"It took all night, I remember there was some investigator Janousek. Big savage, he didn't save his wounds. They let me kneel by the wall, I got my fist in the back of the back, I took the other against the wall, so I didn't look very pretty. They confronted me and others in our group. "

Karel Kukal has already remained in custody. He was once allowed to visit his father, who whispered in his ear, "You have received a letter from the theater that you are being accepted into church."

On December 6, 1948, members of the editorial board of the magazine Za svobodu were tried in the trial of Kukal et al. Karel Kukal was given seven years for "plots against the republic". He was imprisoned in Pankrác for a while, then in Pilsen-Bory and then in the Horní Bříza camp. In 1950, he was deported to uranium mines in the Slavkov region: first to the Prokop camp and then to another camp, marked only by the number XII. or on the Twelve.

Escape from shaft 14 - the idea of "sharp boys"

In all the labor camps, Cookie Scout thought of escaping. He gradually made friends, especially getting closer to Zdeněk Štich, a former student of the Air Force Academy (he was only a year younger, sentenced to ten years in prison for producing anti-communist leaflets).

They thought about getting behind the wires, but each time an unexpected trouble arose. They were not alone in that effort, there were dozens of escapes or attempts to escape from uranium camps, the conditions there were unbearable. Later, “one of us made contact with new Muggles, they were sharp guys. And they suggested we disarm the guard. "

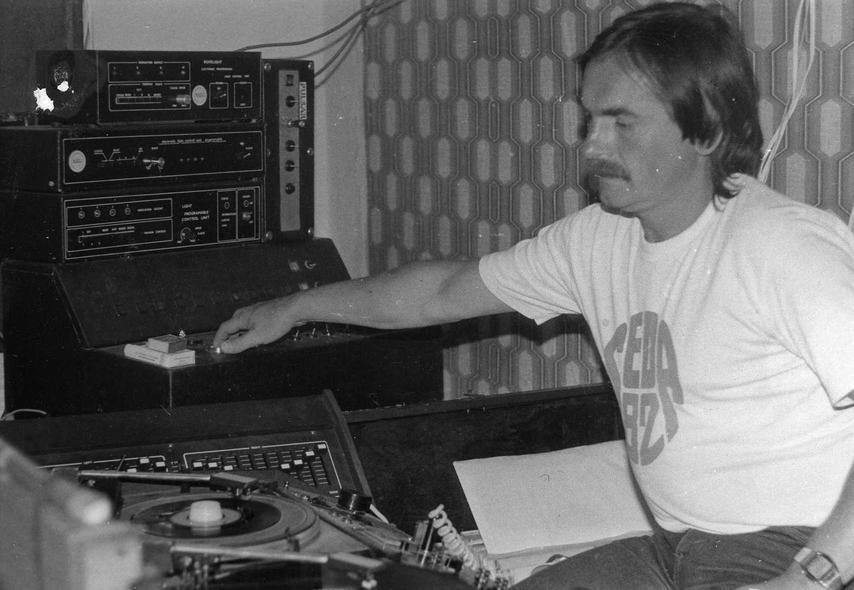

Karel Kukal in 2007 | photo: Post BellumThe prisoners went to work in the shaft, marked only by the number - 14. It was difficult to escape from the camp through the barbed wire and the system of watchtowers, but the shaft, which civilians also worked on, was guarded with less care, standing in the way of freedom only supervisory. The "Muggles" decided that the most promising attempt would be to escape during Sunday night's shift, when a significantly lower number of men and only three bachelors started working. The year 1951 was coming to an end, they had to hurry: in the winter they would not be able to spend the night in the mountains, moreover they would leave traces behind. They chose the night from October 14 to 15.

Eleven prisoners who managed to exchange services so that they could go to work together were to escape. They were Ferdinand Compel, 1929, convicted of high treason; František Čermák (details not known); Miroslav Hasil (1927), convicted of illegal border crossing; Jan Trn (1926), probably a courier, convicted of anti-state activities, including holding a radio; Jan Úlehla (1919), an army officer who fled the Dachau concentration camp during the war, was convicted as commander of an anti-state group; Ladislav Plšek (1925), convicted of high treason; František Petrů, the oldest of the group, he was forty-four years old, details are unknown), Vladislav Roubal (1920), an RAF pilot during the war, convicted of high treason; Boris Volek (1928), convicted of high treason and espionage; Zdeněk Štich and Karel Kukal.

Jiří Levinský also joined the shift - this is the twelfth prisoner who was not expected.

Tábor 12, shaft 14 Post BellumThey came to the shaft, started working, and then pretended that the water pump had broken. At about one o'clock in the morning, Hasil, Trn, and Úlehla were disarmed and persuaded the bachelor Karel Land to go to the workshop with them due to a pump failure - they defeated him, disarmed him, and thus obtained a submachine gun and a pistol. The other prisoners waited at the mining tower.

The same trio pacified the mining master, but when they encountered another guard, Jan Gucký, the firing began and the bachelor collapsed after the intervention. According to Karel Kukal, Gucký was "a newcomer, such a zealous bachelor, he had a submachine gun. Úlehla allegedly aimed at him to put his hands up, he tried to pull the machine gun from his back, so Úlehla shot him. ”No one will know exactly what happened, because there were only people who died soon during the shootout, no one else saw her. , Kukal knew the course of the story. The refugees were startled by the fire, they expected to get out of the shaft quietly and without much violence.

They immediately disarmed the third warden, Zdeněk Dušek (resigned without resistance) - and lowered all the bachelors, including the wounded Gucký and two civilian employees, by elevator or cages into the shaft. Prisoner Levinský, who did not originally run away with the others and was not initiated into preparations, was also to remain in the mine, but in the end the other "muggles" spoke up, so they took him with them.

They all set free and set out quickly. They were led by Úlehla and Hasil, who knew Karlovy Vary, served here as a soldier. Karel Kukal recalls that "Levinský was put in charge of Ferd Compl, he was supposed to watch over him so that he wouldn't do something stupid." And he disappeared into the thicket. Levinsky, as I later learned, and we could assume that, returned to the shaft, pulled the warden out, and, of course, an alarm occurred. Levinsky described the direction we were going. Then they showed him in the camp as an exemplary prisoner who prevented the escape and received mercy. "

I tied a belt around my neck

According to documents from the investigation, one of the guards came to the surface from the shaft by ladders, just as Levinský returned. He helped the others (he could operate a mining elevator), but Supervisor Gucký was already unconscious and soon died. The Bachars called the SNB Crane Emergency Regiment and began combing the area.

Zdeněk Štich photo: Post BellumThe refugees set out on a journey between half past one and two in the morning. Apparently they wandered, they were tired, they didn't get far until dawn, only about ten kilometers from Slavkov (they were heading to Karlovy Vary and wanted to go to the West later). They hid on a slope near the village of Stanovice, where they were discovered by an esenbák from the emergency department and started firing at them. They fought back, then parted.

It is difficult to reconstruct what was happening near Stanovice - however, we know that the first intervention was given to the unarmed Karel Kukal, who was stabbed by the police: neck. I definitely didn't want to get their hands on them. I hung on to the branch, but the branch broke. 'There was no time for further attempts. "

The pursuers of the injured Karel Kukal soon caught up and took him to Stanovice for treatment. What happened to the others? Zdeněk Štich and two other prisoners got to the village, apparently they were looking for help that no one provided them, so they broke into one of the houses, where they collected civilian clothes and some money.

Unlike the friends who continued to escape, Stich remained hidden, either in the chicken coop or in the fire station. The Esenbians found him and took him away. They also caught Boris Volk alive. Unarmed Vladislav Roubal received five gunshot wounds and died. Ferdinand Compla was killed by a blow to the head near the eyebrows. Another dead man, Jan Trn, had his head shot. Jan Úlehla was bleeding after a lung shot. František Petrů had several interventions in his body, including a head shot.

Ladislav Plšek survived a police raid in a forest shelter, climbed in the evening, but instead of trying to get as far as possible, he went back to the camp, where he came across a police patrol and surrendered. Either he wanted to do it because he felt he had no hope on the run - or it was an unfortunate coincidence.

Only two of the eleven refugees, František Čermák and Miroslav Hasil, disappeared from Slavkov.

March around the dead

When Karel Kukal was interrogated and treated, they took him back to the Twelve and threw him into a concrete correction. The same thing happened to Zdeněk Štich and Boris Volk. After a few hours, the bachelors took them to the "apelplatz" - Kukal could not walk, so his friends had to hold him. All the prisoners from the camp had already boarded them, five dead lay in front of them, and the guards placed three captured refugees at their bodies.

Meeting of Muggles in Sternberg, 1990s photo: Post BellumThe others then marched around to see what awaited them if they tried to escape as well. They were not allowed to show their participation: "A Mirek Polák, a foreign soldier, lived with us on the room. And when the others around us 'defiled', around the dead and the three of us alive, he greeted me aloud with my scout name: Hi, Cookie! And immediately they fell on him and led him to a correction under the blows. As he later told me, he was really beaten. "

After the "show", Kukal did not return to the bunker - he completed another round of interrogations and was sent again for treatment:

"However, the horror occurred the next day, when the prisoners were brought on a stretcher and it was Zdeněk Štich. Unconscious, paralyzed, they laid him in the next room. I tried to walk past him when I had to go to the bathroom at night - I looked at him, but he didn't move. His eyes were open. He didn't notice at all. It was an unspeakably sad look to me, like looking into a dead man's eyes. And Zdeněk was actually dead, at least mentally. Then the bachelors came, thinking he was simulating, so they burned his foot with a cigarette. But Zdeněk didn't even move. I didn't realize it until a few weeks later, I heard. "

An article from the period press about the escape of prisoners from Austerlitz shaft number 14 | photo: Post BellumWhen Zdeněk Štich was first interrogated after the escape, he was fine, his statement has been preserved in the archives. Then a brutal investigator apparently put him in charge. The interrogations continued in Klatovy, where Kukal, Volek and other prisoners, who either knew about the planned escape or were suspected by the State Security, ended up. One of the guards, Warden Josef Karolík (born 1930), was also taken into custody. His role in the case is unclear, according to Kukal, he had nothing to do with the plan of the eleven prisoners.

Before everyone was tried, communist security caught the last two escapes. František Čermák arrived in Slovakia and, together with his brother Jozef, planned to cross the border. They found a converter, which, however, cooperated with the StB. Cermak died in a shootout on October 30, 1951.

Miroslav Hasil returned to his native region (he was born in Hrušky near Hodonín), but he acted incomprehensibly carelessly there. On November 27, 1951, he went to a dance party in Dolní Bojanovice, someone betrayed him, and was shot by a police patrol. He allegedly committed suicide.

Three days in the Mining House

The trial of the accused took place from 19 to 21 March 1952 in the Mining House in Jáchymov. When Karel Kukal and I arrived there after decades, all that remained of the former "cultivar" was a ruin surrounded by a corrugated iron fence. The inscription Mining House still stuck to it.

Mr Kukal recalled that the trial was closed to the public: "Only members of the SNB were present, mainly because of the tried Karolík. It was to serve as a frightening example for everyone to see what would happen if they helped the prisoners in any way. The trial lasted three days. In addition to other crimes, we have been accused of espionage and high treason. I was sentenced to twenty-five years, before that I had seven, so it was a total of thirty-two. "

Zdeněk Štich in 2007 | Photo: Post BellumKarel Kukal was lucky, probably also because he stayed in the shaft with Štich and František Petrů until the last moment before the escape. He did not take part in the shootout, after which the guard Tsar Gucký died, he did not have a weapon, so in the end he did not receive a sentence for complicity in the murder. Volka, Plška and Karolol's warden were sentenced to death, their application for pardon was later denied, and on November 11, 1952, they died in Pankrác, Prague. Other prisoners who were not on the run were sentenced to between sixteen and twenty-one years.

The seriously ill Zdeněk Štich was excluded from the trial and in 1953 the authorities suspended his sentence for one year - he was immobile, mentally handicapped, unusable for work. Later, after much effort from his parents and many others, the president gave him a pardon.

Karel Kukal spent the next many years in prison in "fixed" crimes, such as Leopoldov or Carthusians. He was released at 67. After the Soviet occupation in August 1968, he did not expect anything and went with his family to the West. He co-founded the Czech Exile Scout Movement in Switzerland, and at an advanced age he applied to audition for the Bern Opera Choir - and succeeded.

In exile, he also met a former fellow prisoner, journalist and Social Democrat Jiří Loewy, who encouraged him to write memories. At Loewy's instigation and with his help, a book dedicated to the escapees from Horní Slavkov was born. It is called the Ten Crosses - and Kukal writes in it: "Nine Crosses - which is the tenth? It could be Sergeant Josef Karolík. But I think he should bear the name of Zdeněk Štich. But he's alive. He lives, but they killed his soul. And isn't that sometimes worse than murder? ”

Epilogue

Karel Kukal had no news about the fate of his friend for decades - at the end of 1951 Zdeněk Štich only lay, he did not remember anything, he did not know his parents or brother. He couldn't eat himself, he couldn't go to the bathroom.

Zdeněk Štich in front of Karel Kukal's photo |Only thanks to the parents and the help of neurologist dr. He learned to speak, write and count Vlasák from Frýdek-Místek again. But his memory never returned: he only knew what his past had told him - no one could tell about the escape. After his release, ie in the years 1962-1968, Karel Kukal did not meet Zdeněk Štich.

Štich, meanwhile, trained as a watchmaker in a team of the disabled and then worked as a fine mechanic. Only after the fall of communism did he happen to meet again with friends with whom he was in the resistance group Vlasta I in 1948. In the early 1990s, Zdeněk Štich read an article in the weekly Respekt, in which it was written about Karel Kukal. He already knew from people that they had once been friends, that they had been in the camps like twins. He got Kukalovitch's Swiss address and sent him a letter. Then they arranged a meeting at Prague's Masaryk railway station.

"So I stood there with the Metropolitan Diary in my hand as a license plate. And suddenly I see a guy in a leather coat, so somehow it automatically occurred to me that he was an estébák. But not. It was Karel. He came to me, we fell into each other's arms, we sat down in the pub and he told me everything that had once happened. "

They kept meeting, they wrote to each other. Karel Kukal became an essential part of Štich's memory. Zdeněk Štich died in April 2013, Karel Kukal three years later.