Win the war with a hoe: a gardening campaign gave Britain food and morale

In the 1930s, up to 75 per cent of food consumed in Britain came from imports, with around 55 million tonnes a year imported. Half the meat, two-thirds of all cereals, 80 per cent fruit and 90 per cent butter had to arrive on the English market aboard merchant ships. Not all of these goods came from relatively close continental Europe - one-sixth of the meat and half of the cheese was imported to Britain from New Zealand.

Photo galleryView photo gallery |

As the political situation in pre-war Europe became significantly more complicated, it became clear not only at the Palace of Westminster in parliamentary sessions that if the islands went into isolation, the inhabitants would most likely be on the brink of hunger and malnutrition.

Allocations solve only part of the problem

A certain limited solution, how to at least partially control and direct the possible unhappy state, offered to create a food ration system. At least in this respect, the British government surprised with its foresight, elaborating an allocation scheme as early as 1936. Nutrition plans developed by the Departments of Food, Agriculture and Defense .

The organization brought an indisputable result. When the United Kingdom entered the war alongside France on September 3, 1939, the first brochures with allotment tickets have been ready for more than a year and will take only five days to distribute nationwide.

Don't forget to kill the dog: why the British killed pets because of the warVeterinarians had their hands full due to the Second World War in Great Britain. And it was a grim job. They spent their clients' pets, dogs, cats, rabbits. In a panic, their owners decided to let them run out so that they would not suffer for the war. There were at least a million and a half of those animal victims of war and helplessness. |

The final commissioning of the rationing system took another four months, but the situation on the food market was almost perfect. You could read in the press that the royal family also manages the allotment tickets. She went to Hall & Sons for meat, and took eggs, sugar, and ham at the Warren Brothers' Shop on Buckingham Palace Road. And when Eleanor Roosevelt visits Britain a few months later, she gets her own set of tickets.

The system, which did not allow exceptions, seemed fair on the outside and positively motivated the morale of the population. Thanks to him, food prices, at least those that were currently available, have not increased by more than 20 percent. However, even a well-functioning allocation system could not obscure an essential fact. The country, dependent on food imports, could not withstand isolation in the long run.

Let's not wait for help, let's grow ourselves!

However, the development of the situation on the war fronts did not give much reason for optimism either, since the evacuation of the army corps from Dunkirk, British troops went from defeat to defeat. In January 1941, food imports from overseas fell to 14.65 million tons, and the morale of the hitherto more or less unbroken British threatened to starve. How to make sure it doesn't start losing in the background?

The answer was a large-scale agro-campaign, which had also been prepared years in advance. Its architect was John Raeburn, a professor of agricultural economics at Oxford. Raeburn, the original focus of statistics, had more than good practice for this challenging task, for years before the war he was working out national nutrition plans for "unfed" China. And during his internship at Nanjing, he understood that far-reaching food distribution networks would always be prone to outages. And even in peace, let alone during the war.

Food must therefore be ideally made at the point of consumption, he said. Raeburn's first and most important contribution was that he was able to convince Frederick Marquies, Earl of Woolton, who was in charge of the Department of Nutrition at the time. It may seem like a trifle, but the decision to "grow as much food yourself" was crucial to Britain's war effort. And the path to it was not straightforward, as representatives of the opposition thought that Britain could survive on supplies from the United States or Canada were relatively strong.

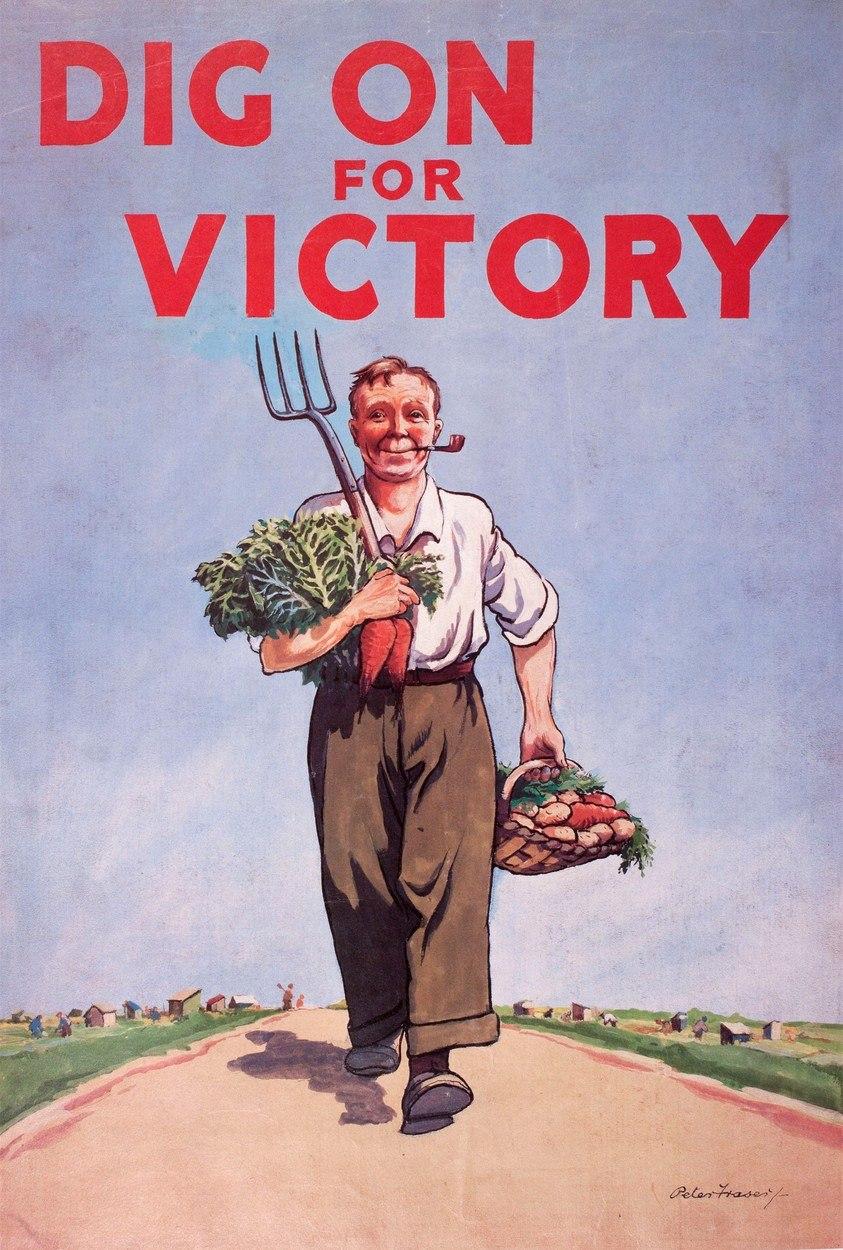

In the end, Raeburn's judgment was confirmed by the German submarine blockade of the islands and the bomber blitz. His campaign called Dig for Victory did not win the British, but it certainly allowed them not to lose.

Fighting is taking place everywhere, in the kitchen and in the garden

True, the subtitle of the nationwide horticultural campaign came into conflict with the Department of Defense because it proclaimed "We don't need ships, we need spades!" themselves.

Gardening also gave a completely different meaning to the lives of civilians. They didn't have to spend their free time just listening to not-so-happy news on the radio, worrying about their lives all day, fearing invasion. They could actively participate, contribute their work. Not everyone can be a soldier, a pilot or a sailor, but they can contribute differently to the fight against the enemy. By picking up a hoe and a rake, they start working on their country's victory.

There was more than enough arable land on the islands. With 15 percent of the population's 50 million serving in various sections of the country's defense, there was a shortage of manpower. That is why the horticultural campaign was definitely not limited to the countryside. The Ministry of Agriculture has distributed over ten million leaflets explaining how to turn into flower-producing fields such as flower gardens in cities.

"It simply came to our notice then. Carrots instead of roses, onions instead of chrysanthemums! Hunger? No, you can compensate for outage system failures with your own crop. You don't need allotment tickets for what you grow yourself. It's a pity for every flowerpot in which no salad or chives grow, "propaganda convinced. And the people in the cities, grieved by the war, heard about it. Not if "you can grow 80 pounds of vegetables on one acre."

In London alone, 1.4 million private home gardens have sprung up, and many more, community-based, have grown under treetops in city parks, school playgrounds, and even golf courses. What about the fact that the golf green has grown here for centuries? Now it was all about Britain.

The castle moats of the Tower of London, Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle were also planted with vegetables. "We are waging the real battle for food," Lord Woolton praised the activities. "Every row, every flower bed saves space in the hold of the convoys with supplies. We can't win a war in the kitchen without battles in our gardens. We will win! ”

The campaign targeted the youngest. Comic book characters of Captain Mrkva and his friend Petr Brambora jumped out of newspaper pages and promotional leaflets, showing that even a small garden means a big change: “Are you too small to carry a hoe? Collect horse manure on the streets! ”

A nation of undefeated gardeners

No place was too small to help. If corn, turnips or pumpkins could not grow on it, the herbs could always thrive there. And even those, as promoted by the regional herbal committees, meant something. They replace and supplement deficient medicines, which went to field hospitals as a matter of priority. Plinths, foxgloves or divisions thus began to replace seasonal tulips and heaths.

And when a German bomb hit Hyde Square and created a huge crater there? "The Nazis wanted to sow death, but we will plant a garden and life in the crater!" Was the agricultural answer. Gardening has become a thoroughbred tool of struggle. And it was not uncommon to see King George VI fertilize with a spade the flower bed at the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens.

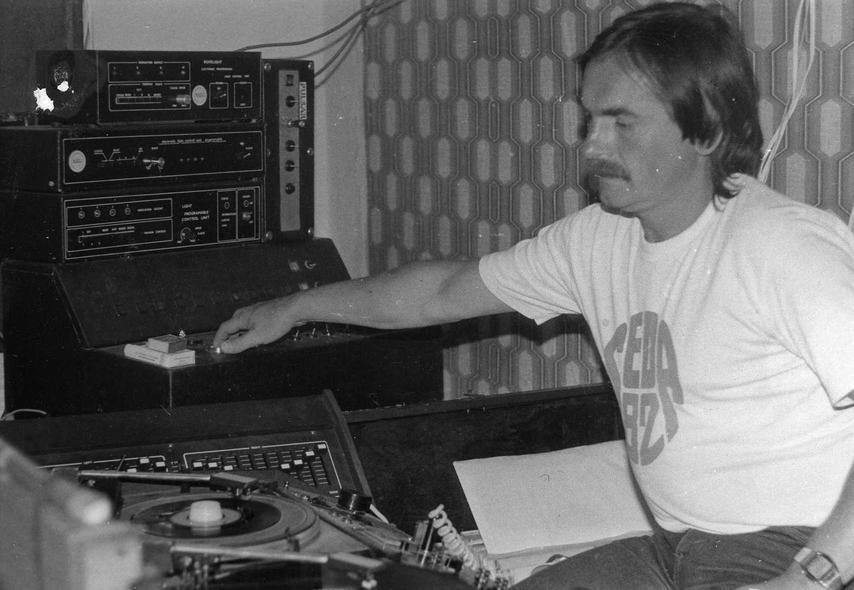

Every Sunday, 3.5 million listeners were able to tune in to the broadcast of the first gardening celebrity, Cecil Henry Middleton, who shared his growing experience. He also urged civilian brigades to fertilize every hitherto unused land. The Women Land Army initiative, a voluntary body of women who wanted to get involved in large fields, was also re-established. There were also songs, poems, striking slogans such as "Dig! Dig! Dig! And your muscles will grow big ”(Kick, kick, kick and your muscles will grow!).

Recipes and recommendations extensively reported on what could be prepared from cabbage, carrots, onions or pumpkins. All newspapers were full of do-it-yourself and culinary tips, such as how long to keep vegetables fresh or how to get rid of pests.

And reports about successful gardeners filled the movie magazines. Cameras were present in Tottenham, for example, where residents created 150 acres of gardens and gardens. "We can defeat German submarines with every square foot of our land," said the proud growers. Gardens were also established in Benthal Green, in the bombed-out East End. It was a much better view of them than the ruined ruins. Flowerbed lines also wound along roads, for example in Manchester. It was not the most fertile field, but it publicly demonstrated its determination to fight.

Hens to every family

Of course, the general lack of food could not be compensated only by vegetables. After the beginning of the naval blockade, most poultry farms had to be killed because there was not enough food for them. The ration system thus allowed you to collect one egg per week, pregnant women or vegetarians were entitled to two.

Therefore, people also started raising hens at home. Even the London Hotel Savoy did not stand aside, its chief manager Hugh Wontner had a part of the parking lot rebuilt for hen breeding, where debates of domestic breeders were held. It was similar with the rabbits, and they were sold by the skins, which were bought by the army.

Pig clubs, community-run pig farms were established in the suburbs. By bringing waste from your own kitchen, you have earned a meat ration for them. About six thousand piglets grew up in London every year. Of course, you could have kept a pig or a cow at home, but they had to be registered. Half of the meat from the defeat was then entitled to the government, which further distributed its share to the army, to public cooking rooms in bombed-out neighborhoods or to hospitals.

The recipe for victory

By 1943, 55 per cent of all British households had two gardens, and dependence on food imports was halved. At the end of the war, the British were able to produce 75 percent of their food consumption. Of course, a number of supplements and substitutes have penetrated the much-simplified gastronomy, such as margarines instead of fats, sausages with a 10% meat content or universal breads rich in vitamins and fiber, but no longer flour.

Today, the half-forgotten Dig for Victory campaign has remained one of the UK's greatest strategic successes. A victory that helped them win the war for supplies as well as the morale of the civilian population.